You have finally received a letter of acceptance from a school in Canada, only to later discover that your application for a study permit has been refused.

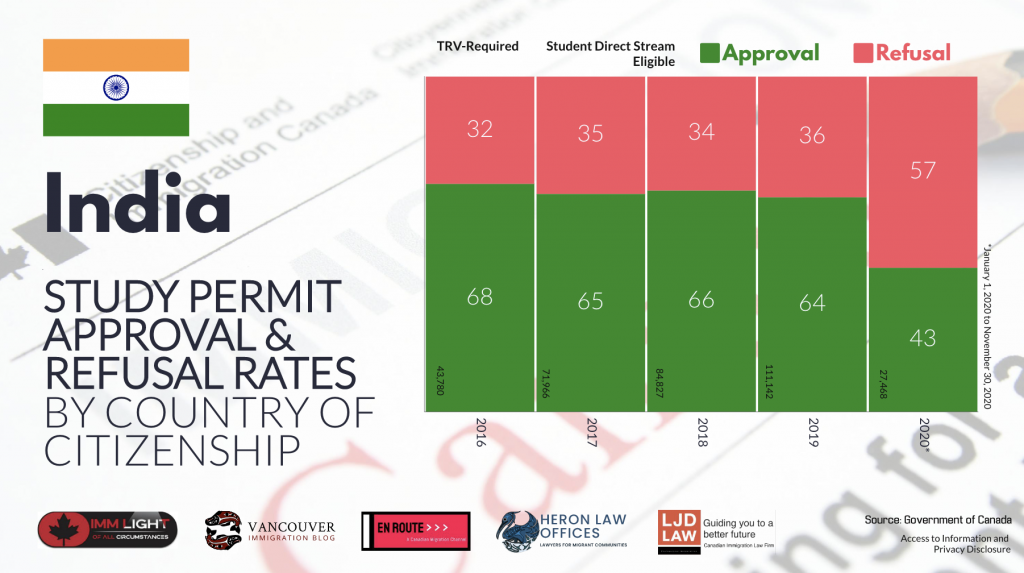

This situation is the reality of more than half of the applicants who applied for a Canadian study permit in 2020 as Indian citizens. Based on data received from the Government of Canada for the period January 1, 2020 to November 30, 2020, approximately 57% of all study permit applications from India were refused. In comparison, the refusal rate for Indian citizens applying for study permits in 2019 was 36%.

This is the reality, despite Indian residents being eligible for faster processing through the Student Direct Stream, with an (IRCC hopeful targeted) 20-day turnaround time, if they can fulfill certain requirements. These requirements include, but are not limited to: having a Guaranteed Investment Certificate (GIC) of CAD 10,000.00, being a resident outside of Canada when applying, presenting a letter of acceptance from a designated post-secondary learning institution, providing proof of payment of the first-year tuition, and scoring high on the English language test.

Although the pandemic and its attendant travel restrictions played a role in the significant rise in Canadian study permit refusals for applications from India, misrepresentation findings involving Indian citizens also contributed to the drop in the number of accepted study permit applications. In Suri v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2020 FC 86, Justice Mason dismissed an application for judicial review, as the visa officer’s refusal to grant a study permit was reasonable because it was based on misrepresentation by the applicant.

Let us examine this as our first case study.

Suri v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) – Misrepresentation: Document Fraud

The applicant in Suri v. Canada is an Indian citizen who applied for a study permit to take up studies at an institution in Ontario. As required, the applicant submitted a GIC as proof that she had the necessary resources to finance her studies in Canada. However, the GIC submitted by the applicant was later confirmed to be fraudulent. The applicant’s father responded to a procedural letter from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), explaining that the family had paid a travel agent in India to prepare the financial documents and that the applicant did not create the fraudulent GIC.

Subsequently, a visa officer sent the applicant a refusal letter stating that pursuant to paragraph 40(1)(a) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, S.C. 2001, c. 27 (IRPA), the applicant was found inadmissible to Canada for directly or indirectly misrepresenting a material fact that would have induced an error in administering the IRPA. Specifically, as stated at para 7, the officer expressed concern that had the GIC not been verified and found to be fraudulent, the officer would have determined that the applicant had the financial resources to cover the cost of her studies and accommodation in Canada, which would have satisfied, although in error, section 220 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, SOR/2002-227 (IRPR):

An officer shall not issue a study permit to a foreign national, other than one described in paragraph 215(1)(d) or (e), unless they have sufficient and available financial resources, without working in Canada, to

(a) pay the tuition fees for the course or program of studies that they intend to pursue;

(b) maintain themself and any family members who are accompanying them during their proposed period of study; and

(c) pay the costs of transporting themself and the family members referred to in paragraph (b) to and from Canada.

As Justice Mason states at para 26:

“While the Applicant explained that the fraudulent GIC was provided by her travel agent, the Applicant is ultimately responsible for all materials in her study permit application…It is unfortunate that the consequences of this misrepresentation is a five year ban on admissibility, but the Applicant failed in her duty of candour. The Officer’s decision was reasonable.”

Binu v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) – Purpose of Visit: Study Plan

In another case, Binu v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2021 FC 743, the applicant was also unsuccessful at seeking judicial review of a decision by a visa officer who rejected her application for a study permit. The visa officer was not convinced that the applicant would leave Canada at the end of her authorized stay in keeping with the purpose of her visit, considering the limited employment prospects in her country of residence, her current employment situation, her personal assets, and financial status.

It is important to highlight that the purpose of a study permit applicant’s visit is to study. Thus, if the officer does not believe that the applicant’s stated purpose of visit is genuine, and the applicant is unable to convince the officer that they will leave Canada at the end of their stay—as stipulated in subsection 216(1) of the IRPR—the officer may reject the study permit application. That does not mean that you cannot apply to extend your study permit, or transition to permanent residence. But it does mean that the visa officer has to trust that you will not stay in Canada beyond your authorized stay, if you run into status issues.

To provide some context, the applicant in Binu v. Canada is an Indian citizen who had been working in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) for the preceding 17 years. As noted by Justice Walker at para 14:

“The focal point of the Officer’s analysis was the Applicant’s study plan and her failure to persuasively explain how the intended UCW program will benefit her future employment plans. The Officer noted that most of the information in the study plan is about the school or program. The plan provides general information which appears to be written in the second person and is not personal to the Applicant, her research or her circumstances. There is little connection to her stated future objectives. The Officer also noted inconsistencies within the study plan as to why the Applicant chose UCW and, in some instances, [there is] no correlation between the headings used and the content of the plan.”

A study permit refusal based on the purpose of your visit is connected to the study plan (also known as the statement of purpose). If the study plan is vague, generalized, and/or inconsistent, this may result in a refusal.

Regarding the applicant’s concerns about bias on the part of the Abu Dhabi office, the applicant mentioned that prior refusals must have influenced the visa officer. However, as stated by Justice Walker at para 2:

the “[applicant] has provided no objective evidence that would establish actual bias or a reasonable apprehension of bias.”

The applicant also argued that the officer’s decision was unreasonable, primarily because of the officer’s consideration of her family ties. She argued that the officer failed to fully explain the analysis applied in this respect. However, a visa officer’s decision is owed a high level of deference by the court. Although the communication of the decision may be brief, it must meet the requirements for a reasonable decision: one that is based on an internally coherent and rational chain of analysis and justified based on the facts and law that constrain the decision maker (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65). As mentioned by the officer in the GCMS notes, they did not give much weight to the applicant’s 17 years of residence in the UAE, as she intended to move to India. The applicant also had weak family ties to India, as she had lived in the UAE—away from her family— for 17 years, making it more likely that the applicant would not return to India at the end of her stay in Canada because she lacked strong family ties in India.

In this matter, Justice Walker states at para 12 that the officer’s decision meets the requirements for a reasonable decision, as:

“the Officer provided a detailed and rational analysis of the Applicant’s study permit application against the requirements of IRPRs and the refusal falls within a range of possible and acceptable outcomes when considered against the facts and applicable law.”

Motala v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) – Officer Must Address Evidence and Provide Explanations per Reasonableness Framework

In Motala v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2020 FC 726, Justice Mosley granted the applicant’s application for judicial review after his study permit application was refused a second time. The GCMS notes stated, at para 6, that the applicant failed to convince the visa officer that pursuing a secondary school education in Canada was reasonable “given the high cost of international study in Canada, and considering the local options available for similar studies, and the applicant’s personal, financial, and familial circumstances.”

The officer was not convinced that the applicant would be a bona fide student who would leave Canada at the end of his stay, in keeping with his stated purpose of visit.

As Justice Mosley mentions at para 18, the visa officer’s reasons for rejecting the applicant’s study permit did not live up to the reasonableness framework established in Vavilov. The officer did not adequately engage with the evidence. Justice Mosley stated at para 14:

“the Officer did not address the evidence that the Applicant was relying on his father’s ability to fund his education and had explained his reasons for wanting to study in Canada. The applicant wished to improve his English language skills with the objective of applying subsequently to attend university in Canada. The evidence submitted indicated that the Applicant’s language skills, as tested by the IELTS exam, were sufficient to attend high school. If the Officer did not agree with that assessment, it was incumbent upon him or her to explain why.”

There was also no explanation as to why the officer considered the cost of the program unreasonable in the applicant’s circumstances. As noted by Justice Mosley, at para 17:

“The evidence indicated that the father had sufficient savings and healthy investments in properties and could support his son financially during his studies in Canada. The Officer may have considered that the cost of a year in a Canadian High School for an international student was unreasonable but that evidently was the choice the Applicant was prepared to make and one that the father could support.”

Patel v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) – Bona Fide Student: Low Test Score for Spoken English

In Patel v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2020 FC 517, Justice Norris granted an application for judicial review after a visa officer rejected the applicant’s study permit application. Although Justice Norris did not agree that the requirements of procedural fairness were breached, he did rule that the officer’s decision was unreasonable.

The applicant is a citizen of India who had applied for a study permit to attend the University of Prince Edward Island. An officer with the IRCC rejected the application because the applicant failed to establish that he would leave Canada at the end of his stay. As stated by Justice Norris at para 2:

…the officer concluded on the basis of a low test score for spoken English that “the applicant would have difficulty effectively communicating and transitioning into successful studies within Canada” and, as a result, was not satisfied that the applicant is a bona fide student “who will be able to successfully complete the study program in Canada.” The officer also noted the applicant’s lack of travel history “which could be used to gauge past compliance to immigration laws of countries with strong migration pull factors.”

The applicant argued that the officer’s decision was unreasonable because it was based on the officer’s position on the applicant’s lack of travel history and the assumption that the applicant’s low language test score was indicative that the applicant was not a bona fide student. Regarding the applicant’s first argument, Justice Norris stated, at para 18, that the officer’s accurate statement that the applicant lacked a travel history “does not amount to anything other than what the officer said: a potentially relevant factor is absent in this application. It does not amount to treating the absence of a travel history as a negative factor, which would have been an error…”

Nonetheless, Justice Norris agreed with the applicant that it was unreasonable for the officer to conclude that the applicant was not a bona fide student based solely on his low spoken English test score. At para 20, Justice Norris quotes Vavilov stating that a decision maker must “justify to the affected person, in a manner that is transparent and intelligible, the basis on which it arrived at a particular conclusion.”

However, as Justice Norris points out at para 24:

“wanting to undertake a course of studies in which one was unlikely to succeed could raise questions about whether an applicant is a bona fide student who will leave Canada by the end of the period authorized for their stay…the connection between the two concepts would appear to be weak at best.”

If we gave decision makers the power to assess, based on a single test result, which applicants would be successful in a particular program, the refusal rate for individuals from India applying for a study permit would probably be higher than 57%.

If an application for a study permit were to be refused because the visa officer believes that the applicant lacks sufficient English language skills to complete his program successfully, as stated by Justice Norris at para 26:

“it was incumbent upon the officer to demonstrate at least some understanding of the level of English language capabilities that were required to succeed in the applicant’s program and to offer at least some explanation for why the applicant’s score of 5.5 for spoken English, considered in the context of all of the other indications of his language skills, fell short of what was required. The failure to do so has resulted in an unreasonable decision.”

Key Take-Away Points

The recent case law pertaining to rejected study permit applications from India provides some useful insight. Critically, Indian citizens continue to submit, oftentimes misled by agents and consultants, false documents in their study permit applications.

Submitting a fraudulent document that is material to the visa officer’s decision to approve or refuse your application—even if you were unaware that the document was fraudulent or if the document was not prepared by you—will almost always lead an officer to reject your study permit application on the ground of misrepresentation, which carries a five year ban on admissibility and eligibility for permanent residence (s.40 IRPA).

It is important for applicants to remember that they are ultimately responsible for all materials submitted in their study permit applications.

Applicants should also prepare their study plan with care and attention, as submitting a study plan that is vague, generalized, or inconsistent may result in a refusal. It is also important to assess your family ties in your home country. If you have weak family ties in the country where you hold citizenship or reside, an officer may reject your application as it could be an indicator that you will not return to your home country at the end of your stay. Officers are looking carefully at ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors, those facts which lead you to want to leave India and those factors which draw you into Canada. Especially, if they stand out on the page, you may need to be proactive in addressing them.

However, we have also seen applications being granted for judicial review after a visa officer rejected the study permit application. Although a visa officer’s decision is owed a high level of deference by the court, they must comply with the standards of a reasonable decision: one that is based on an internally coherent and rational chain of analysis and that is justified in relation to the facts and law that constrain the decision maker (Vavilov). A visa officer must engage with the applicant’s evidence and base the explanation of why the application is being refused on an analysis of that evidence. For example, it would be necessary for an officer to explain why an applicant is not considered a bona fide student—and would thus not leave Canada at the end of their authorized stay—based on a single low test score in spoken English.