Introduction

For many individuals making Canadian immigration applications, the receipt of a letter from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (“IRCC”) highlighting the insufficiency of the evidence provided or the potential allegation or misrepresentation is a very stressful moment.

For those that have received these letters, particularly applicants that are self-represented or sought the advice from a representative that “kept them in the dark” on their applications, this is often where hiring an immigration lawyer starts becoming a major consideration.

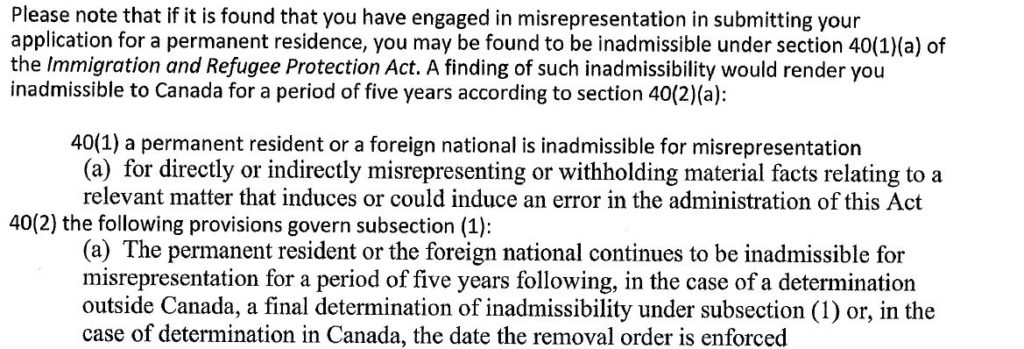

Especially in cases of misrepresentation, where the consequences of a five-year bar are so serious and the definition of misrepresentation so broad, this is where the response has to be timed very carefully, and I dare say it, near perfectly.

Before reading my piece, I would highly recommend pre-reading a few pieces from my senior colleague Steven Meurrens (here – on responding to procedural fairness) and (here – on extrinsic evidence). Steven does a very good job of highlighting the key principles taken from Federal Court jurisprudence.He is indeed a master of administrative law.

Some of Steven’s highlighted principles include:

- the requirement that the Applicant knows the “case to be met” and that the Applicant has the opportunity to respond to extrinsic (i.e. third party) evidence;

- that there are exceptions to the classification of extrinsic evidence, especially where the Applicant ought to have know that material would be consulted (i.e. company website); and

- the idea that a procedural fairness letter cannot “bait and switch” – allege a set of allegations and concerns and then refuse on allegations that were not put forth to you; and

- that if you would like to provide further information (that is pending) you will need to indicate this in your procedural fairness response.

I wanted to add to (supplement) Steven’s work a practical step-by-step analysis of how I breakdown a procedural fairness letter. DISCLAIMER: As with any example, it is not to be treated as overall legal advice. It is not also to suggest that I recommend going at it alone based on my experiences. What I want to do is to encourage a deeper level of thought before the immediate impulse to send back a response the next day stating “it wasn’t my fault for the mistake, it was the consultants” or writing a letter to immigration pleading them to give you leniency. I see these responses too often and often cringe when it is far too late for us to do anything about it (word of truth: there is often a point of no return).

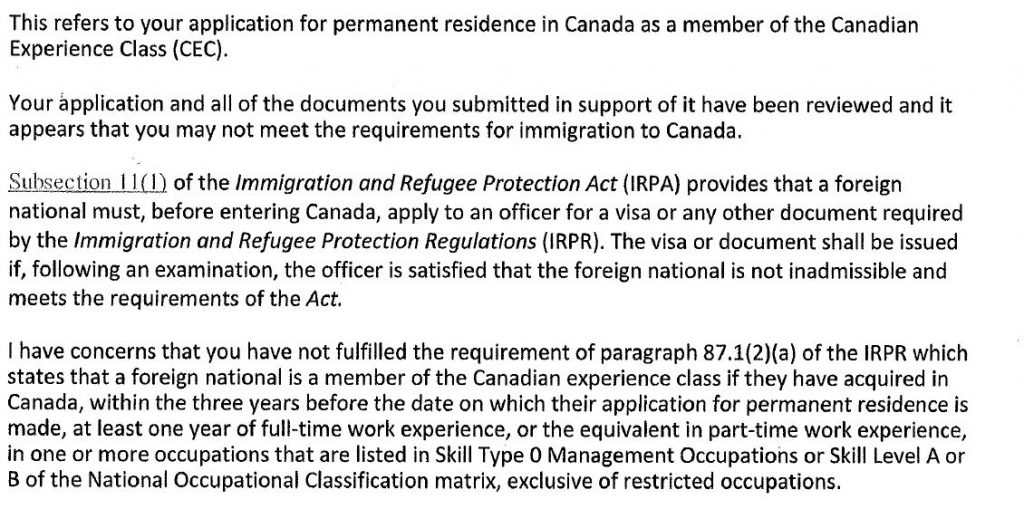

In this piece, I will focus on a situation where an applicant is refused in the context of an economic immigration application (i.e. CEC) but I would suggest these principles are broadly applicable. I also note that much of the case law and jurisprudence, predated Express Entry which has very sped up the process of adjudicating applications. I will not get into the whole discussion of incomplete applications (subject of another post) in favour of discussing solely concerns over the merits and credibility of an Applicant’s application.

My Usual Process

1.Setting out Perimeters Prior to Submission of Application

My recommendations do not start with just the letter itself. Before submitting any application, it is wise to be aware that a procedural fairness letter or a request for further information is very common and more common in complex cases where the facts are messy.

For self-reps, this involves keeping a very good record of all documentation submitted. Scanning copies of all files prior to submission and keeping a running tally of issues you are concerned of can help prepare for the response.

If you are represented by a legal advisor, I stress this time and time again in my posts that you not should have but must demand access to all the materials submitted. I would set guidelines with my advisor to make sure anything submitted in final form is reviewed before it is submitted. You can also tell this advisor that you are aware of the procedural fairness letter process, that you are aware of the process of utilizing Access to Information to obtain a full copy of your file, and that you would appreciate timely passing on of all correspondence in original form. If you do not speak English, find a translator or interpreter to work on your side. You can even use this opportunity to gauge the understanding of your representative of this process and their experiences. A lack of knowledge of these should be an immediate red flag. Make sure to retain your own copy of your immigration file and keep it in an accessible place. I recommend physical scanned copies too as forms often will revalidate or adjust and eventually serve as proof of anything other than an editable form.

I have heard too many horror stories of unlicensed consultants withholding misrepresentation refusal letters or putting in additional documents not at the request of the Applicant. These practices could have a devastating impact on your future application.

2. Studying and Breaking Down the Procedural Fairness Letter

The format of these letters usually follows a set pattern

- The first paragraph or two paragraphs will be rather template language, alleging that you do not meet certain requirements of the Act on the basis of what you have submitted;

- The next few lines will (ideally) set out the specific nature of the allegation. Note that IRCC is not under the obligation to disclose entire transcripts of telephone verification calls or active investigations. The amount of negative evidence disclosed and the source of that evidence should be documented at this stage. IRCC has the duty of procedural fairness with respect to procedural fairness letters and content. Rather than try and explain it, I want to highlight a good summary found in Federal Court jurisprudence. In introducing the law of procedural fairness, Justice de Montigny writes in Chawla v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) 2014 FC 434:

The importance for IRCC of introducing this potential allegation, is that it can cover off potential credibility concerns. If no misrepresentation is alleged at this stage (in content), then it is likely an issue with sufficiency of evidence. However, my experience is that they will do both in most cases.

3. Performing a Background Review

One of the first things to do is order an Access to Information request for the full physical and electronic notes on file. My colleague out in Alberta, Immigration Lawyer Mark Holthe, has put together a good guide on this.

Generally, clients will retain us to go through their previous submission and as well the Electronics notes of the Officer to better understand the discrepancies. The Access to Information process can take 30 days or longer so at this stage you also want to determine when and how you can ask for an extension of time to file a response.

Generally, IRCC is pretty good about giving decent extensions (as this is an important part of procedural fairness). Do not be afraid to ask and certainly do not think that you responding on day 1 vs. day 30 will impact the success rate. While, it may speed up the processing to respond quickly, it could also very well speed up the refusal process.

At this stage, the material and notes you saved from your earlier work will be also very useful.

4. Determining the scope of allegations – insufficiency of evidence, credibility, or both

Start by determining what the alleged concerns are with respect to. In some cases, it may be that the application is insufficient due to documentary evidence. In this case, your goal is to supplement the material. In some cases, there will be credibility concerns over whether you indeed performed the tasks you have stated in an employer reference letter. In those cases, you will need to provide proof by way of additional positive support. In many cases, it is actually your mistake (administrative error, forgetfulness) that has triggered a procedural fairness letter. I like to start by laying out all of the Officer’s concerns and coding them accordingly. Many times they will be lumped into a longer paragraph in a refusal letter so it is important to read over the middle sections of these letters a few times.

5. Corroborating positive evidence and explaining deficiencies

The final step is determining who will be providing support and in what means. In the case of a negative employer verification call, you may need to go to the source for clarification and to seek a rescinded letter of support. You may contact work colleagues or other individuals (customers, partners) with knowledge of your situation. You may want to show proof of projects you were involved with or duties you performed by way of photo evidence. You may have evidence that was not initially submitted that would make a huge difference at this stage.

6. Possibly seeking legal counsel

At this stage, it may be useful to start engaging a lawyer to set out the appropriate legal framework. This is particularly true if the procedural fairness letter leaves something to be desired or appears to be a “bait and switch.” If you do not know the case to be met, you need to indicate this in your response letter and ask for additional procedural fairness. Here, a lawyer can assist in setting out parallel cases and drawing relevant legal principles (such as those Steven epoused in his blog posts)

I Received a Refusal … What next

For an applicant for permanent residence, there is no right to an appeal provided under IRPA or IRPR. The decision at this stage is between the following:

- Seek Reconsideration;

- Seek judicial review

- Seek a new application

On point 3, there obviously has to be a consideration of current eligibility. For many applicants, the processing time renders them no longer eligible (although with the new Express Entry system) this has somewhat changed.

Individuals (and representative’s) have different opinions on this but I like to pursue reconsideration only when there appears to have been a clear or relatively apparent communication error made by IRCC or made as a result of an IRCC request.

While specific to the H&C context I have used the below guidance when seeking reconsideration and was successful on several occasions.

Factors to consider when deciding whether to reconsider:

You must first determine whether a reconsideration of a previous H&C decision is warranted based on the information submitted. The onus is on the applicant to satisfy the officer that the reconsideration should be done. You should consider all relevant factors and circumstances to determine whether a case merits reconsideration. The following is a non-exhaustive list of factors that may be relevant to consider:

- Whether the decision-maker failed to comply with the principles of natural justice or procedural fairness when the decision was made.

- Whether the applicant has requested correction of a clerical or other error (e.g. a decision was made by an officer who did not have the delegated authority).

- If new evidence is submitted by an applicant, is the evidence based on new facts (i.e. facts that arose after the original decision was made and communicated to the applicant) and is it material and reliable. Decide whether that evidence would be more appropriately considered in the context of a new application.

- When additional evidence is presented that was available at the time of the original decision, consider why it was not submitted at the time of the original application. Determine whether that evidence is material and reliable.

- The passage of time between the date of the original decision and the date of the reconsideration.

- Whether there were any concerns regarding fraud or misrepresentation relating to a material fact, in the original decision or with the new submissions.

- If there is a negative decision from the Federal Court after judicial review, you may refuse to re-open if there are no extenuating factors to warrant reconsideration.

I also very much like Justice Phelan’s analysis in Lim v. Canada 2016 FC 217 (see esp. paras 21-24) and try and fit it in wherever possible. As I have written previously as part of a successful reconsideration submission:

Judicial Review

Where I have been able to successfully challenge several refusals of PR applications is on judicial review.

My practice involves, as discussed above, looking closely at the Rule 9 Reasons and ATIP results to breakdown the Officer’s reasoning.

One of my favourite legal cases to cite is an old case, Cepeda-Gutierrez v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) 1998 8667 (FC), (1998), 157 F.T.R. 35. The principle that while not

Judicial Review

Where I have been able to successfully challenge several refusals of PR applications is on judicial review.

My practice involves, as discussed above, looking closely at the Rule 9 Reasons and ATIP results to breakdown the Officer’s reasoning.

One of my favourite legal cases to cite is an old case, Cepeda-Gutierrez v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) 1998 8667 (FC), (1998), 157 F.T.R. 35. The principle that while not

¶ 16 On the other hand, the reasons given by administrative agencies are not to be read hypercritically by a court (Medina v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration) (1990), 12 Imm. L.R. (2d) 33 (F.C.A.)), nor are agencies required to refer to every piece of evidence that they received that is contrary to their finding, and to explain how they dealt with it (see, for example, Hassan v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration) (1992), 147 N.R. 317 (F.C.A.). That would be far too onerous a burden to impose upon administrative decision-makers who may be struggling with a heavy case-load and inadequate resources. A statement by the agency in its reasons for decision that, in making its findings, it considered all the evidence before it, will often suffice to assure the parties, and a reviewing court, that the agency directed itself to the totality of the evidence when making its findings of fact.

¶ 17 However, the more important the evidence that is not mentioned specifically and analyzed in the agency’s reasons, the more willing a court may be to infer from the silence that the agency made an erroneous finding of fact “without regard to the evidence”: Bains v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration) reflex, (1993), 63 F.T.R. 312 (F.C.T.D.). In other words, the agency’s burden of explanation increases with the relevance of the evidence in question to the disputed facts. Thus, a blanket statement that the agency has considered all the evidence will not suffice when the evidence omitted from any discussion in the reasons appears squarely to contradict the agency’s finding of fact. Moreover, when the agency refers in some detail to evidence supporting its finding, but is silent on evidence pointing to the opposite conclusion, it may be easier to infer that the agency overlooked the contradictory evidence when making its finding of fact.

Cepeda-Gutierrez v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) 1998 8667 FC at paras 16-17.

Your case may be one where the Officer has made an unreasonable decision by not weighing or balancing evidence that was positive and focusing only on small non-material details. These omissions are very crucial to challenging the overall reasonableness of the decision against the broad Dunsmuir threshold.

When an application is refused on the merits, there is generally no obligation to provide a running score. If the concerns rise from the Act or Regulations, you do not need to be given another opportunity to respond.

As per Justice O’Keefe in Vikas v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2009 FC 207 (CanLII)

[18] First, the officer was not under any obligation to provide the applicant with a “running score” at each step or to stress all of her concerns which arose directly from the Act and Regulations that bind the officer’s assessment: Abanzukwe v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), [2001] F.C.J. No. 1181 at paragraph 11; Ali v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 1998 CanLII 7681 (FC), [1998] F.C.J. No. 468 at paragraphs 18 to 21; Ashghar v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), [1997] F.C.J. No. 1091 at paragraph 21. The cases cited by the applicant are not applicable because they relate to concerns arising from extrinsic evidence, rather than the Act and Regulations.

However, if they do refuse you on the merits some assessment of the reasons for your refusal on the merits must be presented:

In the recent case of Singh v. Canada 2017 FC 132 argued by my mentor Raj Sharma, this was not done. In Singh, the officer had concerned about Mr. Singh’s qualifying work experience for the Federal Skilled Worker program. In response to the procedural fairness letter, the Applicant corrected his record relating to previously undisclosed work and provided substantial corroborating evidence. Justice Barnes found that the officer’s decision was unreasonable (emphasis added):

[8] Mr. Sharma contends that the Officer paid lip service to Mr. Singh’s response to the procedural fairness letter and that he failed to engage in a meaningful way with the evidence supporting his employment with M. Singh & Co. I agree with that submission. The Officer’s failure to refer to this evidence or to explain why it was insufficient to overcome the initial concern about Mr. Singh’s work experience renders the decision unreasonable.

[9] On its face, the evidence supplied by Mr. Singh was probative and corroborative of Mr. Singh’s declaration of prior work experience with M. Singh & Co. The evidence included a copy of the relevant employment contract, numerous pay stubs, the professional status of the firm, and, under company seal, Indian income tax records. These were the very things the Officer had requested to address his initial concern, and yet Mr. Singh was left to wonder why they were rejected as unreliable. Indeed, these documents carried all of the expected indicia of reliability and, therefore, required careful consideration.

[10] The Officer’s lingering concern about an overlap between Mr. Singh’s accounting studies and his employment was also misplaced. If the Officer had taken care to examine the relevant records, he could only have concluded that Mr. Singh’s accreditation studies required corresponding internship employment. The fact that he was studying and working at the same time was not suspicious – it was expected.

[11] The Officer’s failure to engage with the evidence presented in support of the application before him is fatal to the decision and the decision is, accordingly, set aside. The matter is to be redetermined on the merits by a different decision-maker.

Singh v. Canada 2017 FC 132

In terms of procedural fairness, you want to make sure that any credibility finding or misrepresentation finding was put to you before a decision to refuse was made. There is good case law on situations where Employers or former employees (by way of extrinsic evidence) gave negative testimony and that the recantations or evidence provided in response by the Applicant needs to be examined. In order to determine that the Applicant had lied, there needs to be proof on the balance of probabilities suggesting that this occurred.

Note, however, that there is no automatic right to an interview by a visa officer. These interviews arise on the merit. As restated by Justice de Montigny in Chawla:

[21] There is one further argument made by the Applicants that needs to be addressed. Counsel for the Applicants submitted that the Officer should have interviewed the principal Applicant regarding the credibility concerns after his telephone conversation with Mr. Naresh. There is no right to an interview in such circumstances, and the case law cited by the Applicants in support of their proposition goes no further than indicating that such a duty may arise where the credibility, accuracy or genuine nature of the information submitted by an applicant is the basis of a visa officer’s concern: see Ismailzada v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2013 FC 67 (CanLII) at para 20, citing Hassani v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2006 FC 1283 (CanLII) at para 24. The flexible nature of the duty of fairness recognizes that meaningful participation can occur in different ways, in different situations. As long as an applicant is provided with an opportunity to respond and present his or her submissions, natural justice will be respected: Baker v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 1999 CanLII 699 (SCC), [1999] 2 SCR 817 at para 33.

Conclusion

This is (as my post probably outlined) a very complex and often convoluted area of the law. Making sure initial applications are “judicial review proof” and pre-addressing any gaping holes is by far, the best strategy. Leaving a deficient application in the hands of an Officer can often take more work fixing than it originally would have taken to prepare a strong application in the first place.

I cannot emphasize enough that all Applicants (self-represented or represented) can no longer simply submit forms (or fill out the online eAPR form as it may be) and expect everything to explain itself. There are letters of explanation sections to Express Entry applications for a reason. Representative submission letters or covering letters explain for a reason. No Applicant or Application is ever perfect and the balance of probabilities, more often than not, turns on putting the proper preparation and time into the process and massaging imperfect facts into reasonable explanations.