We recently wrapped up (via consent) a judicial review that has some very important practice implications for us that we wanted to share for everyone’s educational benefit.

The underlying facts are not as important – only to say it involved a study permit extension refusal and our argument of both the reasonableness and procedural fairness of an R.220.1 IRPR allegation for not-actively pursuing studies. We argued in the judicial review that a mere transcript request by the immigration officer was both unreasonable but not procedurally unfair, given the robust R.220.1(4) IRPR regulation and program delivery instructions that govern this space and the type of documentation a student should be afforded the opportunity to submit in their defense.

One of the important steps we took – we often due to take, but now we make sure it is mandatory in all our files – is to file an ATIP simultaneous with the filing of the AFLJR. Traditionally, the idea is you will get the ‘notes’ through both processes (and eventually full disclosure at the Certified Tribunal Record (CTR) stage, but as you will see if you read along, that is not always the case.

The argument of the Department of Justice (DOJ), Counsel for the Minister of IRCC, in this particular case is that the refusal was reasonable as the Officer who made the request for a transcript was considering the R.220.1(1) and R.220.1(4) IRPR provisions when exercising their request for a transcript only and therefore performed a reasonable and fair analysis.

The Court made a Production Order (as they often do) when contemplating granting leave and through that we received the CTR. Weeks earlier we received the results of our ATIP as well, which we are fortunate to have gotten – as practitioners know processing times can be very discrepant, even dragging into the months and years.

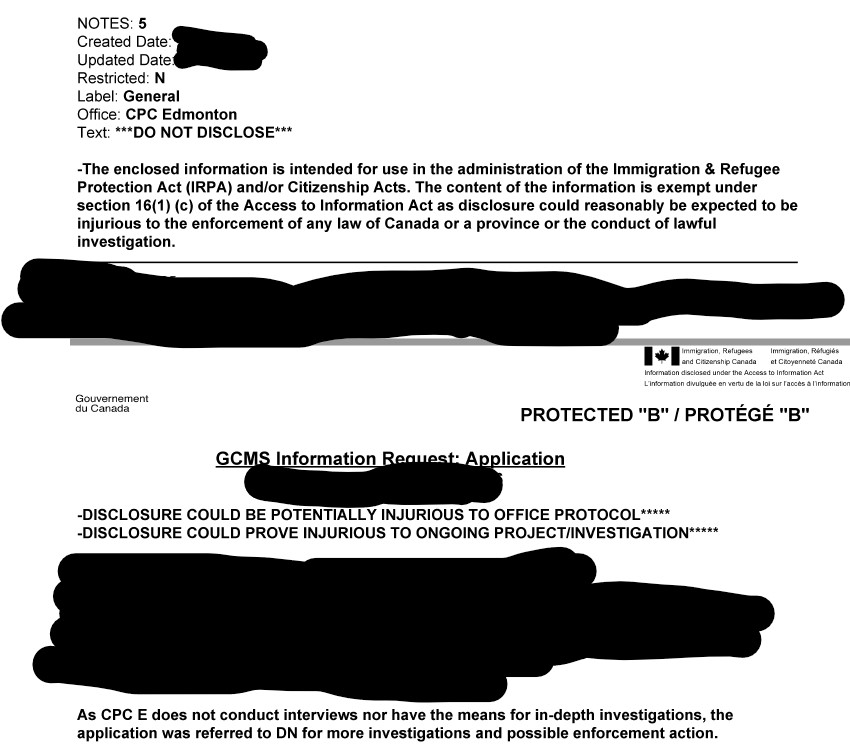

There was one entry, not in the CTR – and arguably that was supposed to have been redacted in the Global Case Management System (“GCMS”) notes – which revealed a lot. This information, again taking what I learned at face value, was not even know to the counsel for IRCC as it directly contradicted the timeline and arguments provided.

I have heavily redacted this entry but wanted to share it as it gives a greater lens into how cases are dealt with between Case Processing Centre Edmonton (“CPC-Edmonton”) and the Domestic Network (“DN”) offices. It also suggests for us as representatives that we need to treat these referrals with a certain level of concern and ask for particulars, request procedural fairness proactively.

The Access to Information Act 16(1)(c) sets out:

16 (1) The head of a government institution may refuse to disclose any record requested under this Part that contain

(c) information the disclosure of which could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the enforcement of any law of Canada or a province or the conduct of lawful investigations, including, without restricting the generality of the foregoing, any such information

(i) relating to the existence or nature of a particular investigation,

(ii) that would reveal the identity of a confidential source of information, or

(iii) that was obtained or prepared in the course of an investigation; or

One can understand looking at the notes (we redacted the client specific notes) that possibly both the content of the investigation but also this acknowledgment that CPC-E is limited in what they can do is information that could impact enforcement of IRPA.

However for us it was the needle in the haystack. It confirmed to us that the initial request for the transcript was routine, and indeed at the point of wanting to initiate an investigation and possible enforcement – they sent it to the local office (DN). However, DN did not request any further documents nor perform any investigation – let alone provide our applicant the opportunity to submit any further documents. Furthermore, many JRs are allowed and sent back for redetermination simply due to an incomplete CTR (see e.g. Tanaka v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 486 (CanLII), <https://canlii.ca/t/jwjpx>)

Had we not ATIP’d, or if we had gotten this section redacted, we would have been fighting a case on an entirely wrong set of facts. Indeed, this strengthened our position significantly and likely led to the early resolution.

I think as counsel we need to challenge evidence and disclosure at multiple steps – during the application/investigative process but just as importantly starting from Rule 9 disclosure, to affidavit evidence, to the CTR. There’s so much occurring behind the surface, in this advanced analytics/data-driven/black box world that needs greater attention.